News Story

Finding Community Among Hard Conversations

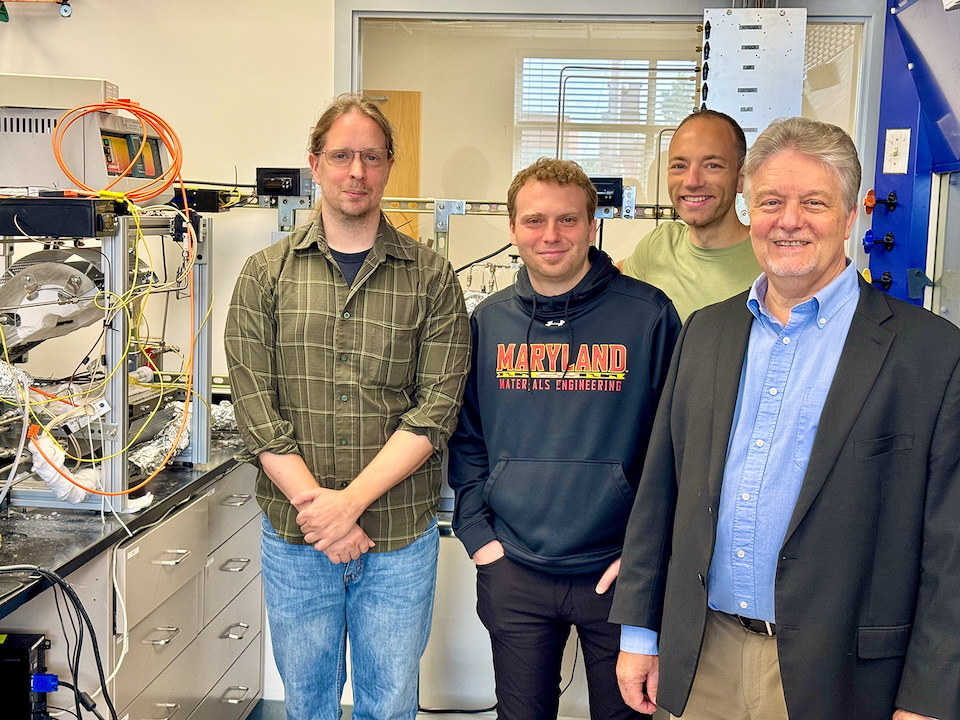

From left: Clark School students Rob Meloni, Jack Drohat, and Kevin Beck, who met and became good friends through Virtus, in 2019.

Shortly after finalizing his college choice, high school senior Rob Meloni found himself up against another big decision: where to live his freshman year at the University of Maryland.

As he weighed his options—which included living as part of the prestigious Honors College or trying his luck for a spot in the cushy Prince Frederick Hall—Meloni came across Virtus, a unique living-learning environment created by the Clark School’s Women in Engineering Program that places male engineering students alongside their female counterparts in a sister program, Flexus. Housed within two floors of Easton Hall, Virtus and Flexus students live, socialize, and study together over the first two rigorous years of college life.

Virtus and Flexus are two of just a handful of discipline-specific living-learning programs at UMD and have a proven track record for boosting retention rates. But what really distinguishes them from other communities is their underlying mission.

“I was drawn to the idea of living alongside other engineers,” says Meloni, who, now a college sophomore, is studying material science and engineering, “but through Virtus, my perspective on how to be part of a successful team, a good classmate, and a good employee in the future has 100 percent shifted.”

That the Women in Engineering Program (WIE) offers support and community for female engineering students isn’t surprising; that it also provides those services to men, might be. In a field where women are still outnumbered by men around 1-to-5, WIE has found that the important way to shift the demographics, create an inclusive class room culture, boost graduation rates across the board, and ultimately build a diverse profession is to invite men into the conversation.

“Sexism is an everyone problem,” says WIE Program Coordinator Sama Sabihi. “If we don’t engage everyone, it puts the responsibility to fix it on women alone. Including men in the dialogue helps them understand what perpetuates sexism in different spaces and is transforming the way they see themselves as part of the problem. If we can place ourselves within that system, we are in a place to make change.”

Bridging the divide

Beyond the traditional living-learning programming, Flexus and Virtus students engage in tailored coursework that touches upon issues of identity and diversity in the engineering field. Students are recruited shortly after acceptance to the Clark School with only two requirements: they must be pursuing an engineering degree, and they must show an interest in having the sort of conversations that promote awareness and change.

In return, Flexus and Virtus students receive instruction and guidance on navigating their first year at Maryland, access to resources, and resume and internship help, all with a focus on identity. During their sophomore year, the curriculum shifts to diversity and inclusion and its relevance to engineering, with topics ranging from power systems to socialization, and how that ties into the workforce and engineering design.

“I admit, I was confused at first as to why there was a male counterpart in the Women in Engineering Program,” says Alexis Burris, an aerospace engineering sophomore. “But men also have a role to play, and it can be hard being a male student and talking about women’s issues. I was surprised at what level they were able to empathize with what [women] face.”

Conversations surrounding diversity and inclusion can be personal, and sometimes uncomfortable. But the familiarity and closeness—a byproduct of living and studying together—quells the awkwardness and fosters the transparent and often vulnerable conversations needed to move the needle.

“People in this program are there because they want to see things change,” says Robert Fink, a sophomore aerospace engineering student. “There’s a lot of unintentional bias, and I think there’s a desire to get some feedback from the Flexus side, on what we, as men, can be doing differently. The Flexus and Virtus programs provides an environment to ask these questions.”

Flipping the narrative

Flexus was launched in 2007 through a gift by the late former Associate Dean Marilyn Berman Pollans to provide a living-learning environment for women pursuing engineering degrees, but from its inception has been open to any student looking for support in the first few years of their engineering education. Young women are often indoctrinated early to the Flexus community through middle and high school programs also sponsored by WIE. Becca Gibbons, who attended the Exploring Engineering at the University of Maryland (E2@UMD) summer program, a week-long sleepaway camp designed for girls to tinker and experiment with engineering projects, knew she wanted to be part of a program like Flexus before even deciding on what university she would attend.

“When you add more people’s perspectives, you can provide service for everyone—and that’s the ultimate goal. Virtus/Flexus bridges the divide in experiences and really made me understand that my sole perspective is not enough.”

— Rob Meloni, Clark School sophomore studying material science and engineering

“Flexus gave me that real sense of community from day one,” says Gibbons, who is now a sophomore chemical engineering student at Maryland. “That was the biggest and earliest impact. Because there are so few women in engineering, it makes us an elite group. That support system flipped the narrative in a way; I feel powerful as a female engineer because I have other powerful women supporting me.”

A 2010 National Science Foundation grant gave WIE the legroom it needed to add Virtus, officially designating Flexus for women, Virtus for men, and mentoring for all. The addition of Virtus and the expansion of coursework that Flexus and Virtus students engage in together, says WIE Director Paige Smith, serve to create allies for women and other underrepresented groups, and to change the culture of engineering.

“There used to be this mindset that if you bring in more women, it will fix the problem,” says Smith. “You really need to pay attention to the inclusion piece, which is the hard work—it’s valuing the experience of everyone at the table without having them leave any piece of their identity out.”

“There’s still so much to do”

Smith and her team realize that not all courses their students take will offer the same level of inclusiveness, nor will the profession. Burris acknowledges that while the Flexus/Virtus community has been a gamechanger for her at Maryland, it’s a modest step in tackling the larger gender issues facing the engineering field.

“The first step in changing anything is to build awareness, and this experience has definitely made me more optimistic,” Burris says. “But I don’t know if it’s resonating with men outside the program or if there are similar programs at other engineering schools. I don’t know if I’ll have that same confidence in the profession once I leave the program at Maryland.”

Smith, who has been with WIE for almost 20 years, is seeing signs that the program is making a difference. Students who attend Virtus and Flexus have a higher retention rate by the end of sophomore year compared to the overall rate for engineering students, which studies show increases the likelihood of graduation. Smith has also found that they return after the program ends not only as student leaders and mentors, but also as alumni, often bringing their companies back to UMD to work with Flexus and Virtus students.

Smith readily admits that, while they have found incremental success in Flexus and Virtus, they are merely one small part of addressing deep-seeded gender, racial, and social disparities, particularly in engineering.

“We recognize that there is so much more to be done,” she says. “This is simply a step. But if the issue resonates with these students and they can carry that to other classes and into the profession, it’s a step in the right direction.”

The programming surrounding Virtus and Flexus continues to evolve and grow; the curriculum is revised each year to include different issues and subjects. A course that lays bare the inequities of engineering design, which was added a few years ago, resonated deeply with Fink, who didn’t realize how far-reaching the omission of gender, race, and ability has perforated the design of everyday products.

“Obviously racism and sexism aren’t new, but how they work out in day-to-day life has been really eye-opening,” he says. “Being a white male, I might never think of that. It’s provided a lot of awareness.”

“It not unusual for underrepresented groups to have an example of a product that wasn’t meant for them. Now people who aren’t in these groups are getting a lesson in non-inclusive design at the start of their engineering education. That will reverberate,” says Haroula Tzamaras (’18 mechanical engineering), who was part of the Flexus community six years ago.

Sabihi explains that the socially conscious caliber of student coming into the Flexus and Virtus programs today makes space for more complex conversations that spur action. In the end, she says, this will lead to more inclusion and diversity in the classroom—and bigger picture, it will produce engineers who value every voice.

“We talk about how the design of a product can never be truly inclusive unless all people are at the table,” says Meloni. “When you add more people’s perspectives, you can provide service for everyone—and that’s the ultimate goal. Virtus/Flexus bridges the divide in experiences and really made me understand that my sole perspective is not enough.”

Published March 29, 2021